Political cartoon from Washington Post by Tom Toles

To help answer the question, we are going to travel back to the past and then to the future.

The Past

First, we travel to the past to answer the question, “Could climate change have ever been prevented?” As I noted in the first of three posts on climate change, we were warned. Perhaps the best time to act was 1965.

That year, President Lyndon B. Johnson's Science Advisory Committee's report "Restoring the Quality of Our Environment" warned of the harmful effects of fossil fuel emissions. The document stated,

“The part that remains in the atmosphere may have a significant effect on climate; carbon dioxide is nearly transparent to visible light, but it is a strong absorber and back radiator of infrared radiation, …consequently, an increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide could act, much like the glass in a greenhouse, to raise the temperature of the lower air.”

The committee’s report relied on recent information about global temperature and carbon dioxide levels from Charles Keeling’s work. The committee blamed fossil fuel burning for atmospheric carbon dioxide rise and that this human activity had a worldwide influence stating,

"Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment … By the year 2000, the increase in atmospheric CO2 will be close to 25%. This may be sufficient to produce measurable and perhaps marked changes in climate and will almost certainly cause significant changes in the temperature and other properties of the stratosphere.”

But how realistic was that? Were we or the world going to stop using fossil fuels at that time let alone the fact that renewables like solar and wind were in their infancy?

Naomi Oreskes, professor of the history of science at Harvard University, and co-author of Merchants of Doubt, said that much of the present-day damage of climate change was preventable, and if we had started working on it back in the 1960s and 1970s, we would have had plenty of time to switch to renewable energy and other greenhouse gas free technology. Unfortunately, she noted that some scientists back then thought if we wait and see what happens, it will be too late to stop by the time we find out.

The Present

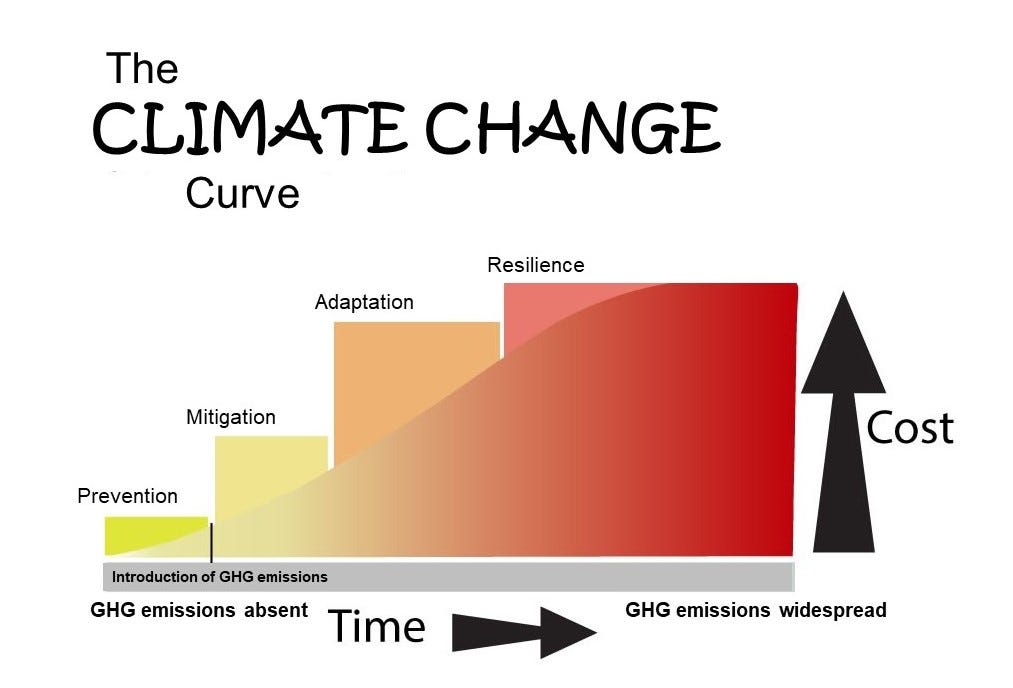

The introduction and ever-increasing cumulation of greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere is akin to the introduction of an invasive species with an ever-increasing human and financial cost.

We really can’t prevent some level of climate change now. Carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas causing global warming, stays in the atmosphere for thousands of years. Global warming and climate change will affect future generations even if we stop generating greenhouse gases today. So, the next step is mitigation.

Mitigation

Mitigation of climate change requires reducing the flow of heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere by reducing sources, such as burning fossil fuels for electricity, heat, or transport, or improving capture sources, such as oceans, forests, and soil. It aims to avoid significant human interference with Earth's climate and stabilize greenhouse gas levels in time to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, protect food production, and enable sustainable economic development.

And if we can’t mitigate, the next step is adaptation.

Adaptation

Adaptation to life in a changing climate requires adjusting to current or future climate. The aim is to mitigate climate change threats like sea-level rise, extreme weather, and food shortages. This can involve using climate change's benefits, such as longer growing seasons and higher yields in some locations. Governments are considering development plans to manage extreme disasters, protect coastlines and deal with sea-level rise, manage land and forests, plan for drought, develop new crop varieties, and protect energy and public infrastructure.

Finally, the last step is resilience.

Resilience

Resilience to climate change is the ability to plan for, respond to, and recover from dangerous climatic occurrences with minimal damage to society, the economy, and the environment. This involves policy, infrastructure, services, planning, education, and communication. Building climate resilience involves a holistic and multi-dimensional approach to improve communities' social, human, ecological, physical, and financial capacities to adapt to climate change.

What has to be done now?

The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) study issued a report in March 2023 indicating that the world may exceed its most ambitious climate target of 1.5 degrees Celsius over preindustrial temperatures by the early 2030s. The world would then pass a dangerous temperature threshold pushing the planet past catastrophic warming, unless nations drastically transform their economies and immediately transition away from fossil fuels. Climate calamities will be too terrible for humans to respond.

In September 2023, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) issued a report noting that the world is not on track to meet the long-term goals set out in the Paris Agreement of 2015 for limiting global temperature rise and needs to commit to decisive action. The Paris Agreement requested each country to outline and communicate their post-2020 climate actions, known as a nationally determined contribution (NDC) or intended nationally determined contribution (INDC). It is a non-binding national plan highlighting climate change mitigation, including climate-related targets for greenhouse gas emission reductions.

The report noted in the figure below a possible future and urged all parties to rapidly and deeply reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. According to the IPCC, limiting global warming to 1.5 °C (>50 percent probability) with little or no overshoot requires reducing global GHG emissions by 43, 60, and 84 percent below 2019 levels by 2030, 2035, and 2050. The median time frame for worldwide net zero CO2 emissions is the early 2050s and net zero GHG emissions is the early 2070s.

The Future

Now let’s travel to the future.

Bill McKibben, environmentalist and journalist, wrote a piece in 2019 for Time magazine, Hello From the Year 2050. We Avoided the Worst of Climate Change — But Everything Is Different, in which he imagined what it would be like if we started to address climate change more dramatically beginning in 2020. People became more aware due to extreme climate events. Renewable energy sources were starting to take over the energy market and there was tremendous pushback as journalists exposed denial and disinformation and the legal community began a campaign to change things. Although we avoided the worst of climate change by 2050, things were quite different than they were in 2019.

Society did not escape without severe consequences. The most dangerous physical changes in human history occurred. The temperature kept rising and a large section of the West Antarctic ice sheet fell into the ocean, with a rising sea level measured in feet. The East Coast of the United States had moved inward a few miles. Forest fires occurred year-round and hurricane/typhoon seasons lasted for many months. The melting permafrost released ancient remains containing germs from extinct illnesses. Drought and desertification forced large numbers of Africans, Asians, and Central Americans to relocate creating almost a billion refugees. In many places, the heat had become intolerable with nighttime temperatures above 100°F making outdoor work nearly impossible for weeks and months. Things were dire but civilization survived. And all the above assumed we did something more dramatic starting in 2020. It’s now 2023.

For another credible view of the future consequences of climate change and a great read, see Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future.

The same month that the UNFCCC issued their call to action the International Energy Association issued a report with some grounds for guarded optimism. In the last two years, there has remarkable progress in developing and deploying some key clean energy technologies such as solar power and electric vehicles. While greenhouse gas emissions keep rising, they noted that there's still a path to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 and limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, to avoid the worst effects of climate change. A faster transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy is needed in the next decade but annual spending on this will have to increase from $1.8 trillion to $4.5 trillion.

So, is the glass half full or half empty? Will the community of nations redouble their efforts? It’s never too late to do the right thing.

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.